Long ago and far away, in a time before Walmart, big chain stores, and shopping malls…when Amazon was simply a river in South America…when color television, phonographs, and transistor radios were high-tech… when “Diners Club” was the only credit card, and few people had one- small town folks did their shopping, cash or credit, on Main Street.

In our small town, my family’s business was Chief Home and Auto Supply, and for many years, “the store” operated in the middle of the main drag, Hamilton Street, across from the post office. The store was a magical place, where folks could find almost anything they needed or wanted. We could deliver, and customers could “charge it on their accounts,” and pay over time.

The store smelled like tires; I remember the chewing gum machine on the counter- how the penny John Carter always had for me would bring forth two brightly-colored squares- (three if I jiggled the handle right). I always hoped for yellow and pink. The red ones were cinnamon, and a little hot. I remember the row of console televisions lining one wall, and the row of shiny bicycles. I remember my dad’s office up front.

At Christmas, a big aluminum tree stood on a bed of fake snow in the window, glistening in the glow of a revolving, multi-colored light. How cool, and space-age! I remember the toys: aisle after aisle of any plaything a child of the 1960’s could want- everything he had seen on Saturday morning cartoons’ commercials, or she had circled on the pages of the Sears and Roebuck catalog. I remember waiting inside the store for the Christmas parade-listening for the band, running back and forth to the window until it was time go out in the cold. First came an honor guard of veterans carrying the flag. The Catamount redcoat marching band followed, the beautiful majorettes twirling their batons. Then came floats, old cars, the county high school bands, armies of Boy and Girl Scouts throwing candy canes, more floats, and finally- at the pinnacle of excitement- Santa Claus himself!

Afterwards, people might stop by the Bradley and Weaver drug store lunch counter or the U-S Cafe for a bite to eat- others might head to Cannon’s department store, Belk Gallant, or McCrory’s five and ten. Many poured into “Chief Auto.” Christmas shopping had begun!

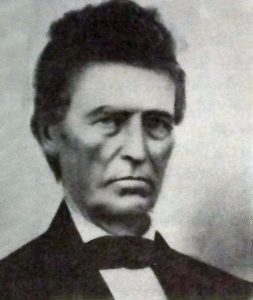

Everyone should experience the joy of working retail at Christmas. It tests and builds character. My own initiation came as a young teenager, in the early ‘70’s. I was to wrap presents. Easy, right? Wrong. I was to wrap packages under the hot light of Grandaddy’s watchful eye- and Grandaddy was a man of no waste. The paper mustn’t overlap more than one-sixteenth of an inch. If the seams met exactly, all the better. The three pieces of tape allowed must be miniscule. I remember grabbing a bow to stick on a toaster, and Grandaddy growled, “Don’t put a bow on that- it was on sale.” Try wrapping a basketball, a chainsaw, or a tennis racquet under those conditions. My boy cousins did have it easy- assembling bicycles in the unheated warehouse- and putting trampolines and swing sets together. Come to think of it, Grandaddy probably made his rounds there, too, to keep them on task. But I digress. Back to downtown, 1965.

We didn’t see much of Daddy between Thanksgiving and Christmas. He worked from eight in the morning until ten at night, six days a week. After church on Sunday, we let him put his feet up in his easy chair, smoke his pipe, and read the Atlanta Journal. Our own tree (not the aluminum kind), usually bought from the Green Spot grocery, went up the Sunday before Christmas, with big colored lights, shiny bright ornaments, and dangly strands of icicles. My mother, my brother, and I provided the Christmas joy and high spirits; Daddy provided the dragging in of the tree, installation of the lights, and a fair bit grumbling…but who can blame him?

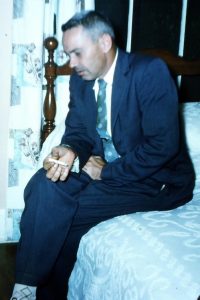

Christmas Eve, the longest day of the year, always finally arrived. After the last ping-pong table and washer-dryer had been delivered, the last lay-away picked up, and the last dollar taken to the night deposit at the bank, Daddy came home, bone-tired, used-up, worn-out. Mother had a graham cracker cake waiting, warm from the oven. After cake, my brother and I climbed in Daddy’s lap. He read the story of the Savior’s birth from Luke 2 as only he could, making us feel like we were right there with the terrified shepherds when the night sky split open and a glorious heavenly warrior shouted “Good News!” Then, he read “The Night Before Christmas,” and we could almost hear “the prancing and pawing of each tiny hoof.” Then off we hustled to bed- and when we finally fell asleep, he unloaded Santa’s sleigh- I mean his pickup truck. (It’s a lucky child whose family owns the toy store).

Late one such Christmas Eve, after assembling my brother’s pedal-firetruck, and my first bicycle, my parents set out Santa’s bounty for a very good little girl and a moderately well-behaved little boy. (My brother might tell the tale differently, but don’t believe him). Then, at last, they settled down for a long winter’s nap. Suddenly, a clatter arose- and Daddy sprang from his bed in bleary-eyed confusion- but it was to answer the jangling telephone, not to see Saint Nicholas.

The clock said two a.m., and another bone-tired, used-up, worn-out daddy was on the line.

“Mr. Cochran?”

“Yes?”

“This is Jim _______. You may not remember, but I bought a set of tires from you last summer.”

“Uh-huh?”

“I’m sorry to call at this hour… I hate asking…”

“Asking…what?”

“I drive a truck- I should’ve been back by early afternoon- but I just now got home. There was a big snow in Kentucky- then the road over Monteagle was closed down… Mr. Cochran, I’ve got no Christmas for my kids.”

“Oh…all right… I see. Can you meet me at the store in… say, twenty minutes?”

“You bet I can. Thank you, Mr. Cochran.”

“Glad to. I’ve got children, too.”

And so, on a dark, quiet, cold winter’s night, on a deserted small-town main street, the lights came on in the store. Two bone-tired, used-up, worn-out daddies loaded up another pickup truck- with a doll and tea set, a baseball, bat, and glove, two sets of roller skates, a fire truck, a set of building blocks and a teddy bear, a parcheesi game, along with yo-yos, jacks, slinkys, a jumprope and a train whistle for the stockings- along with something pretty from housewares for Mom.

“I should have told you, Mr. Cochran, I couldn’t pick up my check. I can’t pay you right now.”

“We’ll put it on a ticket. Just come in next week and see me.”

Two daddies shook hands beneath the stars, still bone-tired, but no longer used-up. “Merry Christmas, Mr. Cochran. God bless you.”

“Merry Christmas, Jim. A little ice on Monteagle can’t stop Santa, can it?”

My daddy never told the story, but after he was gone from us, my mother did. I was not surprised.

Time never stops, and in its fast-flowing current, life, culture, and people change. Chief Home and Auto, Bradley and Weaver, Cannon’s, McCrory’s, the Green Spot and U-S Cafe, along with many thousands of other small-town, family-owned businesses, are no more than history and memory. Little girls no longer ask for Chatty Cathy dolls, and today’s little boys wouldn’t know what to do with a set of cap pistols and a cowboy hat. Sadly, interaction with a screen seems to be replacing interaction with other people.

Some things, however, do not change: the world is broken. People are a mess. We keep trying to find happiness and fulfillment in pride, selfishness, and greed- when strangely enough, humility, love, and giving are the secret to a satisfying life. Isn’t that what that long-ago baby in the manger- Emmanuel, God with us, Yeshua, “The LORD is Salvation”- showed us?

Kindness may come with a cost- but be kind. The investment in humanity will pay off, in ways we may or may not see. Love with words and deeds. Extend grace. Be the blessing someone desperately needs. Be assured: someone is watching and will follow your example- be it good- or bad. Listen. Smile. Give- and forgive. Kindness has the power to change the world- even it’s merely the little world around us– for the better.

I learned a lot in the many years I worked at “the store”- starting with how to wrap a room full of packages with a smidgen of paper and a dab of tape. And do you know- Grandaddy’s guardianship of the paper paid off. This Christmas, my brother will use that same roll to wrap all his gifts, as he has for decades- and there is enough for fifty more years, if anyone wants it after he’s done. Oh- and if you ever need to deliver a ping pong table, make sure the straps are good and tight.

Peace, love and joy to you. Merry Christmas.